Adapted from the program notes for Symphonie Fantastique, written by Jane Girdham

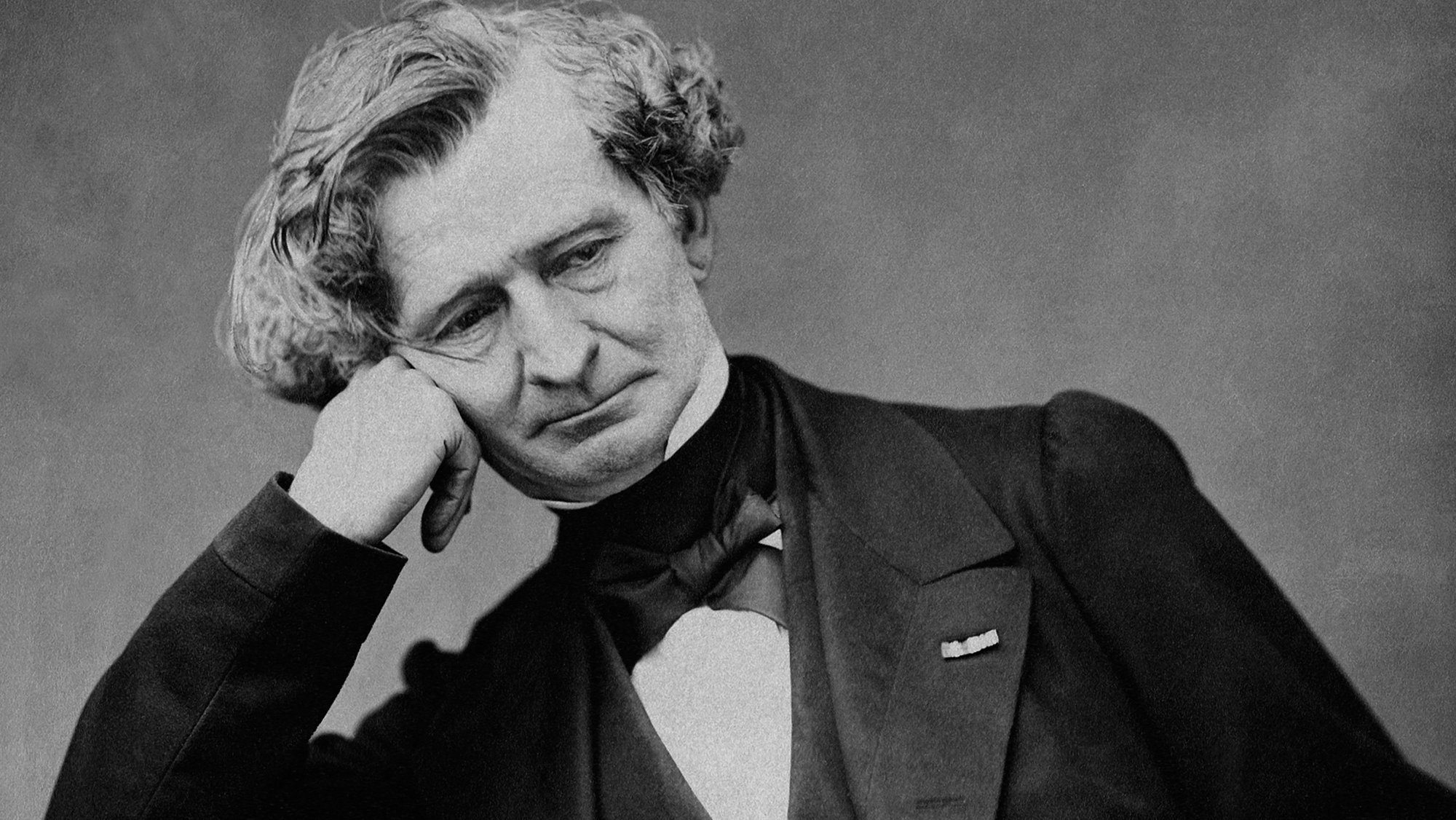

Berlioz is recognized for his imaginative and expressive use of orchestral instruments, and his

interest extended into writing a treatise on orchestration, which was first published in 1844 and

later updated by Richard Strauss. In the Symphonie Fantastique (1830) he introduced

instruments not yet familiar in symphonic music: two harps in the waltz, an English horn (a

deeper oboe) in the third movement, and a high E-flat clarinet and bells in the finale. He also

used the same two obsolete instruments that Wagner used in Rienzi: an ophicleide, and (in the

finale) a serpent. Here the serpent’s traditional association with choral music made it

particularly appropriate for playing the Dies Irae chant because of, in Berlioz’s own words

(translated by Theodore Front), “its cold and awful blaring.”

Berlioz’s care over instrumental color also extended to performing technique. He often gave

detailed instructions in his scores as to how instrumentalists should play their instruments. For

instance, string players are given specific instructions such as “very sharp tremolo,” and timpani

players (four of them are needed in the last movement) are told at times to use wooden drum

sticks, at others sponge-headed ones.

Berlioz was a young composer living in Paris when he attended a performance of Shakespeare’s

Hamlet in English (which he did not speak), with the Irish actress Harriet Smithson playing

Ophelia. He was immediately obsessed with her, even though he was not able to meet her for

several years. His Symphonie Fantastique is intimately bound up with his as yet unrequited

love. Berlioz was determined that his audience should understand the very personal story of

each movement, so he wrote a narrative for the audience to read at the premiere in 1830. The

1845 version is given here, in a translation by Nicholas Temperley.

Note

The composer’s intention has been to treat various states in the life of an artist, insofar

as they have musical quality. Since this instrumental drama lacks the assistance of

words, an advance explanation of its plan is necessary. The following program,

therefore, should be thought of as if it were the spoken text of an opera, serving to

introduce the musical movements and to explain their character and expression.

First Movement

DAYDREAMS – PASSIONS

The composer imagines that a young musician, troubled by that spiritual sickness which

a famous writer [Chateaubriand] has called le vague des passions [the vagueness of

passion], sees for the first time a woman who possesses all the charms of the ideal being

he has dreamed of, and falls desperately in love with her. By some strange trick of

fancy, the beloved vision never appears to the artist’s mind except in association with a

musical idea, in which he perceives the same character–-impassioned, yet refined and

diffident–-that he attributes to the object of his love.

This melodic image and its model pursue him unceasingly like a double idée fixe.

That is why the tune at the beginning of the first allegro constantly recurs in every

movement of the symphony. The transition from a state of dreamy melancholy,

interrupted by several fits of aimless joy, to one of delirious passion, with its impulses of

rage and jealousy, its returning moments of tenderness, its tears, and its religious

solace, is the subject of the first movement.

Second Movement

A BALL

The artist is placed in the most varied circumstances: amid the hubbub of a carnival; in

peaceful contemplation of the beauty of nature–-but everywhere, in town, in the

meadows, the beloved vision appears before him, bringing trouble to his soul.

Third Movement

IN THE MEADOWS

One evening in the country, he hears in the distance two shepherds playing a ranz des

vaches [alphorn call; literally “rows of cows”]; this pastoral duet, the effect of his

surroundings, the slight rustle of the trees gently stirred by the wind, certain feelings of

hope which he has been recently entertaining–all combine to bring an unfamiliar peace

to his heart, and a more cheerful color to his thoughts. He thinks of his loneliness; he

hopes soon to be alone no longer… But suppose she deceives him! … This mixture of

hope and fear, these thoughts of happiness disturbed by dark forebodings, form the

subject of the adagio. At the end, one of the shepherds again takes up the ranz des

vaches; the other no longer answers… Sounds of distant thunder… Solitude… Silence…

Fourth Movement

MARCH TO THE SCAFFOLD

The artist, now knowing beyond all doubt that his love is not returned, poisons himself

with opium. The dose of the narcotic, too weak to take his life, plunges him into a sleep

accompanied by the most horrible visions. He dreams that he has killed the woman he

loved, and that he is condemned to death, brought to the scaffold, and witnesses his

own execution. The procession is accompanied by a march that is sometimes fierce and

somber, sometimes stately and brilliant: loud crashes are followed abruptly by the dull

thud of heavy footfalls. At the end of the march, the first four bars of the idée fixe recur

like a last thought of love interrupted by the fatal stroke.

Fifth Movement

SABBATH NIGHT’S DREAM

He sees himself at the witches’ Sabbath, in the midst of a ghastly crowd of spirits,

sorcerers, and monsters of every kind, assembled for his funeral. Strange noises,

groans, bursts of laughter, far-off shouts to which other shouts seems to reply. The

beloved tune appears once more, but it has lost its character of refinement and

diffidence; it has become nothing but a common dance tune, trivial and grotesque; it is

she who has come to the Sabbath… A roar of joy greets her arrival… She mingles with

the devilish orgy… Funeral knell, ludicrous parody of the Dies irae, Sabbath dance. The

Sabbath dance and the Dies irae in combination.

What Berlioz’s own narrative fails to tell is the sheer originality of the symphony. Its five

movements follow the traditional plan of the four-movement symphony but with two “dance”

movements, the Ball (II) and the March to the Scaffold (IV). Five movements were not

unprecedented: Beethoven himself had used five in his “Pastoral” Symphony No. 8, also to suit

his program. But where Beethoven represented the sounds of nature, Berlioz created

characters and a plot that develop throughout the work. The musician (Berlioz himself) is

obsessed with the Beloved but his love eventually turns sour, while the Beloved, who is

represented throughout the movements by a melody (or idée fixe) that gradually changes

character from ideal to macabre, turns from being an object of adoring passion into a cackling,

manic witch.

After a slow introduction to the first movement, the unattainable Beloved’s melody is

introduced as the main melodic material. It is romantic, expressive, and long-breathed, and the

object of the musician’s desires. The second movement, a waltz, places the musician at a ball,

where he glimpses her every so often amid the swirling dancers. The slow movement is set in

the country, where two shepherds (English horn and off-stage oboe) call distantly to each other

before the mood gradually turns dark as he remembers her less happily. At the end, the

shepherd calls out again, now with no reply.

The last two movements portray opium-induced nightmares. The Beloved is absent from the

inexorable march of the musician to the scaffold (he has killed her) until the guillotine is about

to fall, as if his last thoughts before his head rolls are of her. Finally in the last movement she is

transformed into an ugly cackling witch on a shrill E-flat clarinet as their devilish rituals begin.

Phrases of the Dies Irae from the Requiem Mass are heard, first low and straightforwardly, then

cruelly turned into an ungainly dance parody. Eventually a Round Dance begins in fugal style,

growing in density and volume, sweeping the orchestra towards the end.

![SBSO Full Logo (color) fullwhite[Converted]](https://www.saginawbayorchestra.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/SBSO-Full-Logo-color-fullwhiteConverted.png)